By Geoffrey Smith

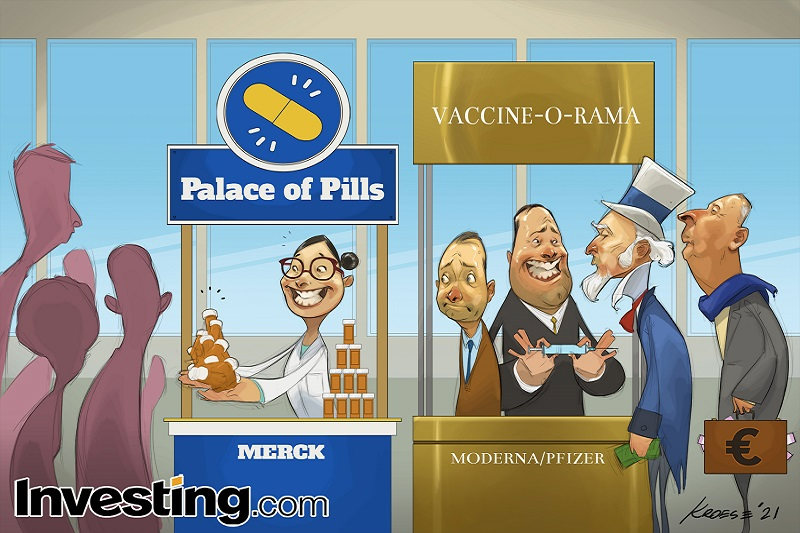

Investing.com -- The stock market loved it, but euphoria at Merck's (NYSE:MRK) announcement last week that it may have an effective Covid-19 drug that can be taken in pill form is probably premature.

To be sure, the news is nothing to be sniffed at. The interim results of a curtailed phase 3 trial – typically the last in a series required for new drugs – suggest very strongly that the drug is effective in preventing serious illness and death and is free from significant side-effects.

If that is confirmed by regulators, then the world will have its first effective Covid treatment in tablet form – easier by orders of magnitude to mass-manufacture, distribute and administer than vaccines.

However, it is unlikely to be a standalone answer the biggest problem in bringing Covid-19 under control: the still-low vaccination rates in poorer countries. Fewer than 20% of India’s 1.38 billion population are fully vaccinated. Of Africa’s seven most populous countries, accounting for over 730 million people, only South Africa has a vaccination rate over 6%. Molnupiravir will not stop the disease from spreading and mutating freely among these people.

An antiviral pill is in the first instance a remedy, not a prophylactic. It is not an adequate substitute for mass-vaccination. Merck’s press release suggested that the drug does have some prophylactic quality, but the clinical trial has only focused on treating people who already have Covid.

As such, the drug is likely to have a greater impact – at least initially – in the rich world, where it appears excellently suited as a second line of defense in combating ‘breakthrough’ infections among the vaccinated, and as a safety net to the substantial minorities who have refused or been unable to take vaccines.

Whether state-backed health insurers will want to underwrite a $700 course of tablets for people who have refused to take a $20 vaccine is another matter, especially if it makes people more inclined to accept the first and best line of defense against Covid.

Before that stage is reached, though, there are more pressing questions to answer. The most pressing regard its safety.

Merck excluded pregnant women from its test and insisted on patients abstaining from sex during the treatment, suggesting that it has not ruled out the risk that the drug’s technology, which deliberately fouls up the way the virus replicates itself, may have unintended consequences. Obviously, such things are beyond the scope of a 29-day trial.

Assuming the drug is ultimately approved, Merck looks likely to do well enough out of it. It already has a $1.2 billion preliminary sales contract with the U.S., and others are lining up to place orders: Australia ordered 300,000 courses earlier this week.

But there is no guessing how much it can make from the drug in poorer countries, given the lack of public detail about pricing in its preliminary agreement with generic drug manufacturers in India. Moreover, it is unlikely to have the field to itself for long. Roche and Pfizer (NYSE:PFE) both have antiviral remedies in the pipeline.

All of that, naturally, is good for consumers, health systems and anyone who wants a return to pre-Covid conditions as soon as possible. But the real pandemic game-changer remains mass-vaccination. The rewards of delivering that seem likely to be bigger, at the end of the day, than the rewards awaiting Merck shareholders.