By Geoffrey Smith

Investing.com -- Tech’s day of reckoning has arrived.

The sector has ridden a 12-year wave of easy money to sell dreams of unimaginable wealth on narratives that have depended less and less on substance, and more and more on buzzwords. At a time when capital can earn 4% today for no risk at all, those peddling fortunes built on cash flows in five years’ time are increasingly struggling.

And that's no bad thing.

Weaker parts of the tech sector have been slimming down for a year or more already. The significance of recent layoffs is in the fact that they have been at companies that until quite recently were widely considered to be invulnerable, due to their commanding position in the new megatrends of the age, be it streaming, social media, e-commerce, or self-driving cars.

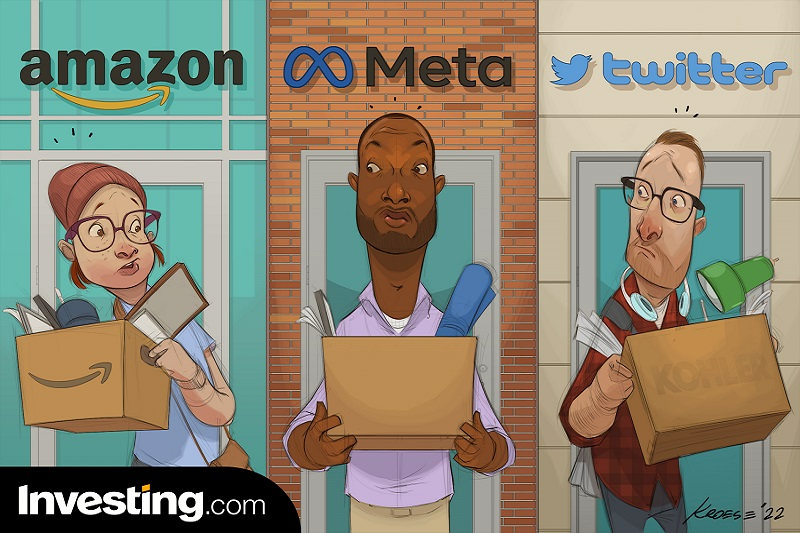

Facebook owner Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META) is cutting 11,000, or one in seven of its staff worldwide. Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) is reportedly looking to cut 10,000, admittedly a much smaller share of its 1.5 million-strong workforce. Twitter, under the uniquely aggressive culling of its new owner Elon Musk, is cutting numbers by half.

Stripe, Snap (NYSE:SNAP) and Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX), along with Lyft (NASDAQ:LYFT) and Uber (NYSE:UBER) have all trodden the same path this year. Every day, the list lengthens: this week alone, Cisco Systems (NASDAQ:CSCO) has announced it will cut 4,100 jobs, while streaming device maker Roku (NASDAQ:ROKU) said on Thursday it will cut 200. In both cases, that’s around 5% of the total.

One common theme running through the narrative is the weakness of the advertising sector, which has both cyclical and structural elements.

The structural element is that Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), which accounts for over a quarter of the world’s mobile devices and a larger share among richer consumers, has made it all but impossible to sell more highly-priced targeted ads by tightening its privacy policy. Apple users appear to like this feature, so there is little chance of it being reversed.

The cyclical element is essentially a reversion to the mean: ad spending, which is never more than a derivative of consumer incomes, boomed during the pandemic when manufacturers had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bombard the bored and homebound with ideas on how to spend their stimulus checks. It started shrinking when inflation started eating into disposable incomes and that process accelerated as fears of job insecurity spread around the world.

Consumer confidence is now at an all-time low in countries like the U.K. and Germany.

Another common thread is the over-confidence bred by the extraordinary and patently unsustainable policy settings of the pandemic years. Too many people believed either that the good times would last forever, or that, more charitably, the pandemic would accelerate irreversible long-term trends to digitization and automation. Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg and, on Thursday, Amazon CEO Andy Jassy both admitted to having over-hired.

A third thread is that too many of the sector’s long shots have turned out to be simply too long. While the core businesses of companies like Meta and Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL) make good money, the pet projects they are supporting on the company balance sheet are losing money hand over fist.

Altimeter Capital’s Mark Gerstner begged Zuckerberg last month to halve spending on his Metaverse projects to a maximum of $5 billion a year. Chris Hohn, head of London-based hedge fund TCI, directed the same criticism at Google owner Alphabet this week, calling out CEO Sundar Pichai for blowing $20 billion over the last five years on its “Other Bets” division, whose largest element is the Waymo self-driving venture.

The over-expansion at Big Tech has been bad not just for the companies’ shareholders (Amazon, Meta, and Alphabet are down by 43%, 67%, and 32%, respectively, this year), but for the U.S. economy in general, sucking up talent that could have been deployed more productively.

“We have a shortage of talent in Silicon Valley," Altimeter's Gerstner said. "Meta and other large companies have made it very difficult for start-ups to hire.” Gerstner said he’s “confident that these employees will find replacement jobs and quickly be back to work on important inventions that will move us all forward.”

The economic data, so far, appear to be proving him right. While the number of layoffs is clearly increasing, the number of people filing initial claims for jobless benefits has not risen markedly from a 60-year low. Clearly, those being laid off have plenty of opportunities elsewhere. Enough soft landings at the personal level give the economy a good chance of achieving one at the macro level.

That reality may go some way to explaining the resilience of U.S. consumption in recent weeks and months, even though the outlook has clearly darkened. More consumers may be losing their jobs, but if they are confident enough of finding a new one quickly, they will be less afraid of dipping into savings to keep up their consumption levels.

Against such a backdrop, despite the obvious human distress, there are good reasons not to be too downhearted at Big Tech’s downsizing. What has been seen so far is more an exercise in capital discipline and the unwinding of excess, not a sign of a vicious downward spiral. As days of reckoning go, the market has seen much worse.