We’ve been here before. In the spring of 2023, the bond market rallied sharply, effectively forecasting a rate cut by the Federal Reserve.

But the punt turned to tears as the Federal Reserve continued raising interest rates, causing bond prices to sink and yields to spike.

Rate hikes are probably history this time, but the market’s recent estimates that rate cuts are near appear premature once more.

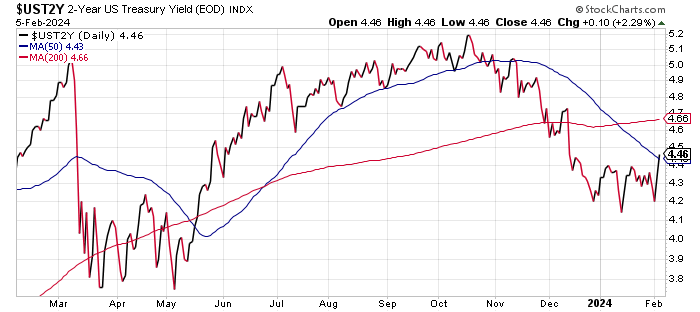

In mid-January, the 2-year rate fell to 4.14%, marking the point of maximum bullishness for market expectations that a March rate cut was likely. But Fed officials continued to push back on the idea.

Surprisingly strong economic news for fourth-quarter GDP and January payrolls added to the view that growth remains resilient and so rate cuts can wait.

It took a few weeks, but the market is once again getting the message and revising expectations accordingly.

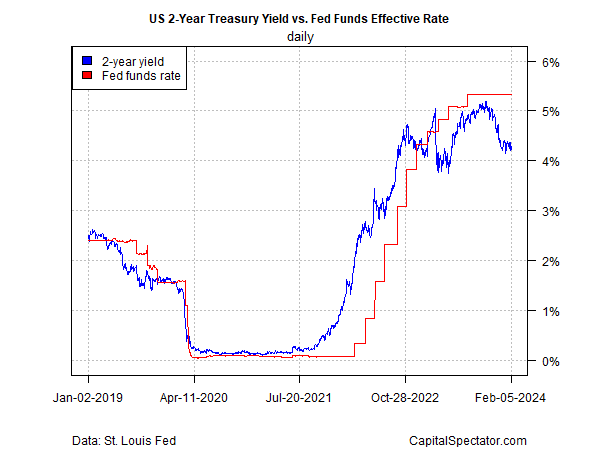

The front-row seat for monitoring the Treasury market’s implied bet on the future relative to Fed policy can be seen in the 2-year yield vs. the Fed funds rate.

The sharp relative slide in the 2-year rate vs. Fed funds lately has left a yawning gap between the two. Taken at face value, the widespread suggests that the market is confident that a rate cut is imminent.

The mismatch between what the market is, or was, expecting and the Fed’s plans became sufficiently misaligned that Fed Chairman Powell felt compelled to go on national TV on Sunday and explain:

“We feel like we can approach the question of when to begin to reduce interest rates carefully.”

Minneapolis Federal Reserve President Neel Kashkari on Monday extended the not-so-subtle hint by writing that Fed policy is less restrictive for economic growth than it appears and so the central bank can be patient with rate cuts.

“This constellation of data suggests to me that the current stance of monetary policy may not be as tight as we would have assumed given the low neutral rate environment that existed before the pandemic,” he advised.

It doesn’t help that yesterday’s ISM Services survey data for January reports the largest monthly increase in the prices-paid component since 2012.

Although there’s reason to be cautious on reading too much into one month of survey numbers, economists at Wells Fargo conclude:

“The ISM services report is not what policymakers at the Federal Reserve wanted to see” because “it’s hardly supportive of the case for rate cuts.”

Not surprisingly, Fed funds futures are now assessing the probability of a March rate hike as a low probability (roughly 17%). The new estimate for a cut is now the May 1 FOMC meeting, which is currently priced at a roughly 66% probability.

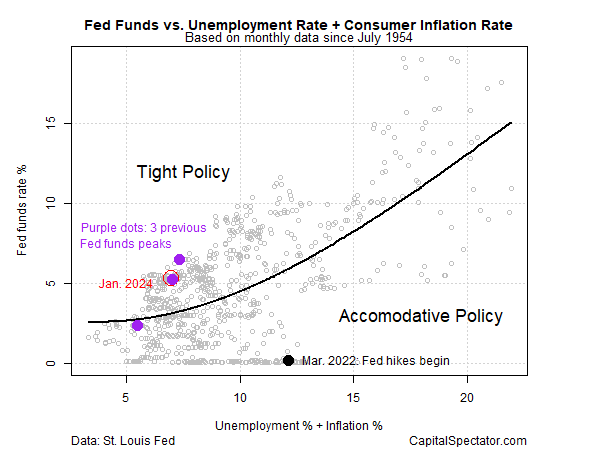

A simple model that uses consumer inflation and unemployment suggests Fed policy is still moderately tight and so the case for easing is plausible.

But the market’s track record over the past year-plus has been dead wrong and so confidence in the so-called wisdom of the crowd.

By some accounts, the fact that this is an election year suggests that rate cuts are likely, presumably on the view that the Fed doesn’t like to be seen as playing politics as the nation chooses a president.

Maybe, although the notion of playing politics cuts both ways since both leaving rates unchanged or cutting can look suspicious, depending on your political views.

The bottom line: the timing of rate cuts is unclear, again. May could mark the start for a run of dovish policy, but the Fed, as ever, is looking for incoming to provide support for pulling back from restrictive policy.

The fear is that a repeat of the 1970s is brewing, when inflation receded, the Fed dropped its guard, and inflation revived.

A 1970s redux is unlikely, in part because the Fed is aware of the danger this time and wants to preserve recent progress on taming inflation.

On that note, the market will be hyper-focused on next week’s consumer inflation data for January. Meantime, expect the bond market to remain gun-shy until new numbers give it reason to revive its dovish outlook.