In the podcast, we covered several global macro themes and investment opportunities.

Macro is back, and it’s impacting markets everywhere you look.

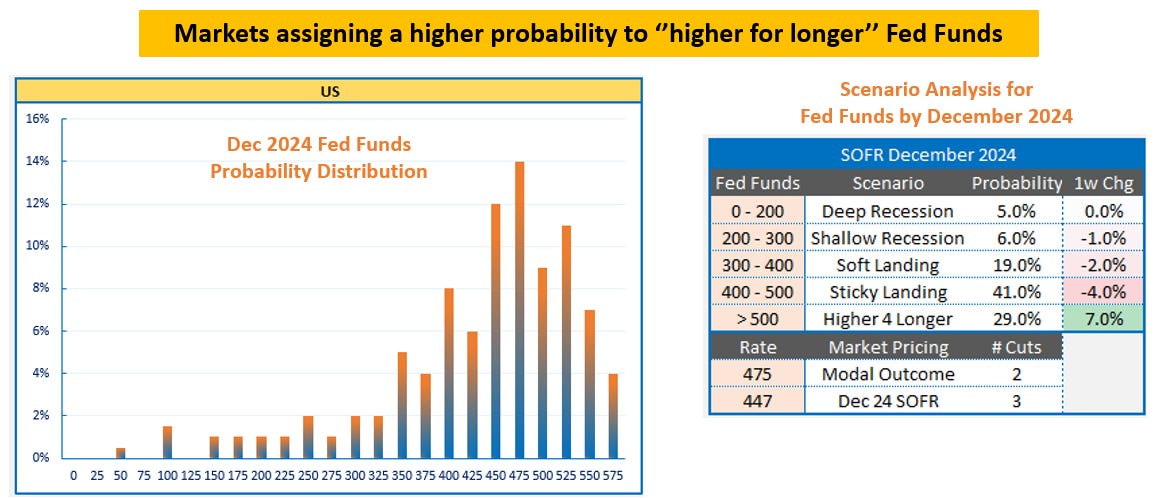

We discussed the chart above: it shows the market-implied probability distribution for where Fed Funds will end in December.

I derive that market-implied distribution and table of scenarios from options on the SOFR December 2024 contract - in other words, I am looking at what fixed-income option traders are willing to pay or get paid for different scenarios this year.

The distribution is quite interesting.

The modal outcome (the most observed in the distribution = the highest bar) is 475 bps or only 2 cuts! That’s even less than the 3 cuts the Fed projects in their Dot Plot.

The recession tail is thin (11% probability only) but it still exists, and therefore it pushes the mean outcome towards 3 cuts - in line with the Fed.

Markets aren’t assigning a meaningful recession premium anymore to bond market pricing, and have fully converged with the Fed Dot Plot here.

‘‘Buy insurance when you can, not when you must’’ applies here?

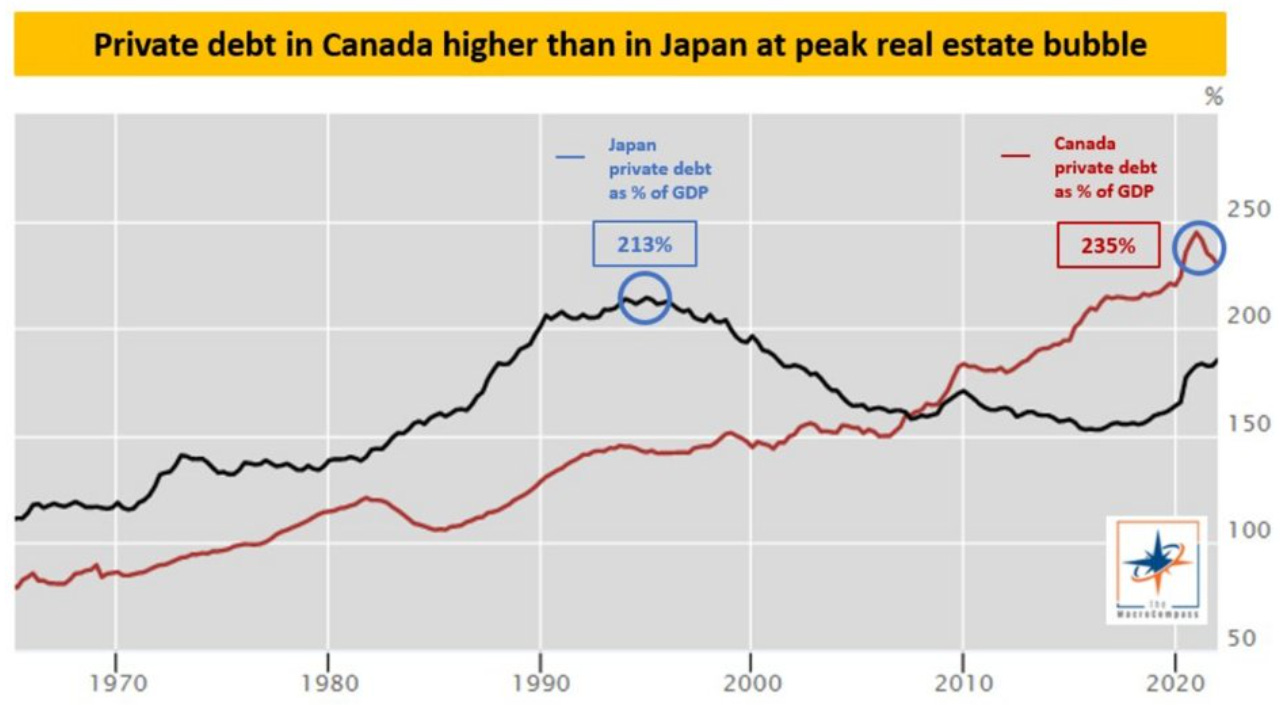

All Central Banks in the world have followed the Fed in a sharp hiking cycle.

But not all economies are equipped the same way to handle the effect that higher interest rates bring.

In this episode, we discussed a few of them including Canada.

The chart above shows how the Canadian private debt as a % of GDP is larger (!) today than it was in Japan at the peak of the real estate bubble.

Nevertheless, the Bank of Canada has raised rates aggressively and it’s now planning to only ease marginally - again, following the footsteps of the Fed.

Is that credible?

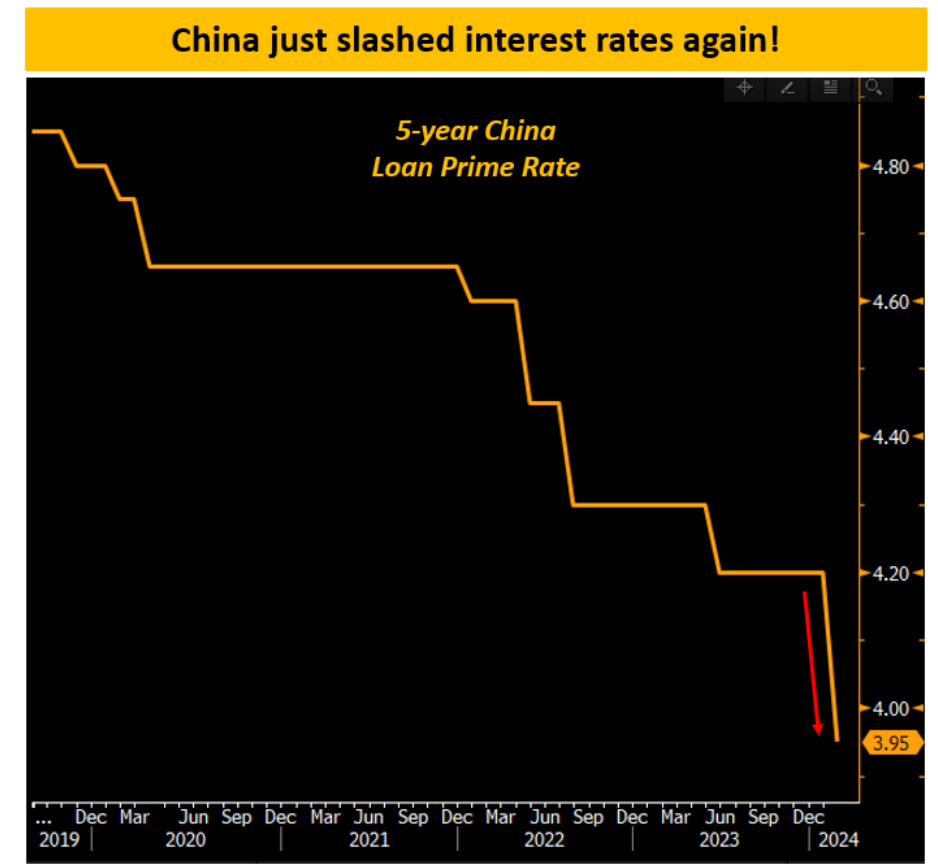

We also looked at China.

China recently cut the 5-year Loan Prime Rate which is the reference rate used for mortgages, and so the idea was to reduce household borrowing costs for Chinese people.

As other policy decisions have failed, authorities now hope that cutting mortgage costs will do the trick.

But that’s unlikely to work.

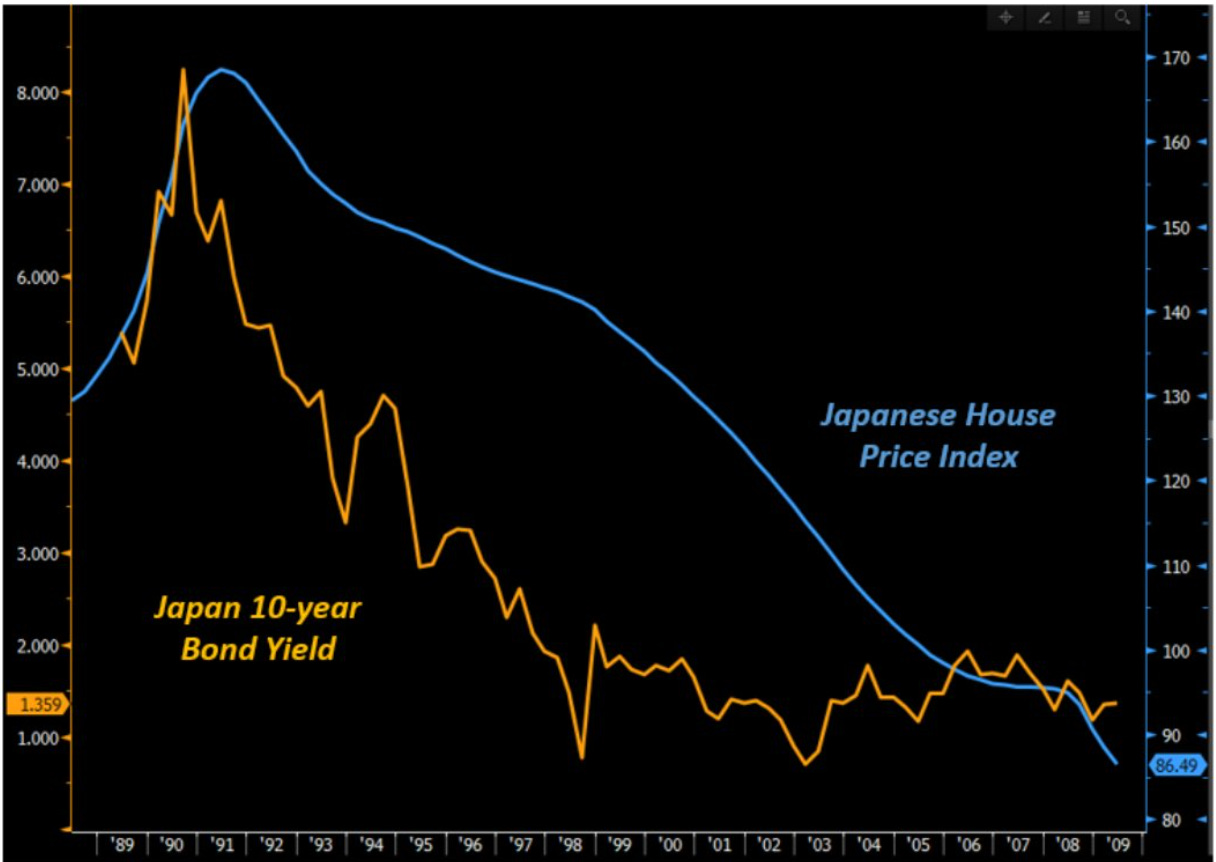

In the early 1990s the Japanese real estate bubble burst and the world’s most famous balance sheet recession unfolded – the Bank of Japan lowered and kept rates to 0% for decades after and nothing happened.

Look at this chart: Japan 10-year bond yields (orange) dropped from 8% to 1% and yet Japanese house prices (blue) kept falling!

When you hit balance sheets hard through a deleveraging process, asking people to take on more credit isn’t going to work even if rates are low.

We also discussed a few trade ideas on the back of global Central Banks trying to imitate the Fed even if domestic economies appear much more fragile.

Disclaimer: This article was originally published on The Macro Compass. Come join this vibrant community of macro investors, asset allocators and hedge funds - check out which subscription tier suits you the most using this link.