Some analysts who favor one or two indicators to forecast US recessions have had a rough year. The reliance on a generally robust predictor may yet prove its worth in the months ahead. But so far the months-long calls by some pundits that recession is near have been wrong, or at least premature.

There’s always another recession approaching, of course, but the timing aspect is the tricky part. Some of the forecasts have relied on what has long been celebrated as a so-called flawless predictor: the US Treasury yield curve. The historical record, numerous studies point out, show that when long rates fall below short rates, economic output turns negative in due course.

But while the 10-year-less-3-month spread turned negative nearly a year ago, the US economy continues to expand and the odds remain low that an NBER-defined recession has started or is imminent.

Some recession forecasters have doubled down on the recession call and now say they’ll be vindicated by the start of a downturn in 2024. Maybe, but it’s useful to review some simple truths about analyzing the business cycle.

First, looking beyond a few months is effectively a coin flip. The US economy rarely turns on a dime, short of an exogenous shock, such as the pandemic that hit in 2020. Otherwise, it’s reasonable to run some basic modeling to nowcast the current scenario and make some reasonable projections about how output will evolve over the next 2-3 months. Beyond that, there are just too many factors that are unknown to confidently assess what could happen, or not.

Second, relying on a handful of indicators is asking for trouble. The yield curve is a valuable metric and it has an impressive track record of anticipating recessions. But every indicator fails at some point, typically with little or no warning. The solution: Model the business cycle with a carefully selected, diversified mix of indicators to minimize noise and maximize signal. It’s not perfect, but compared with the alternatives, it’s substantially more reliable–assuming you don’t abuse it by, say, making recession forecasts 6 months or a year into the future.

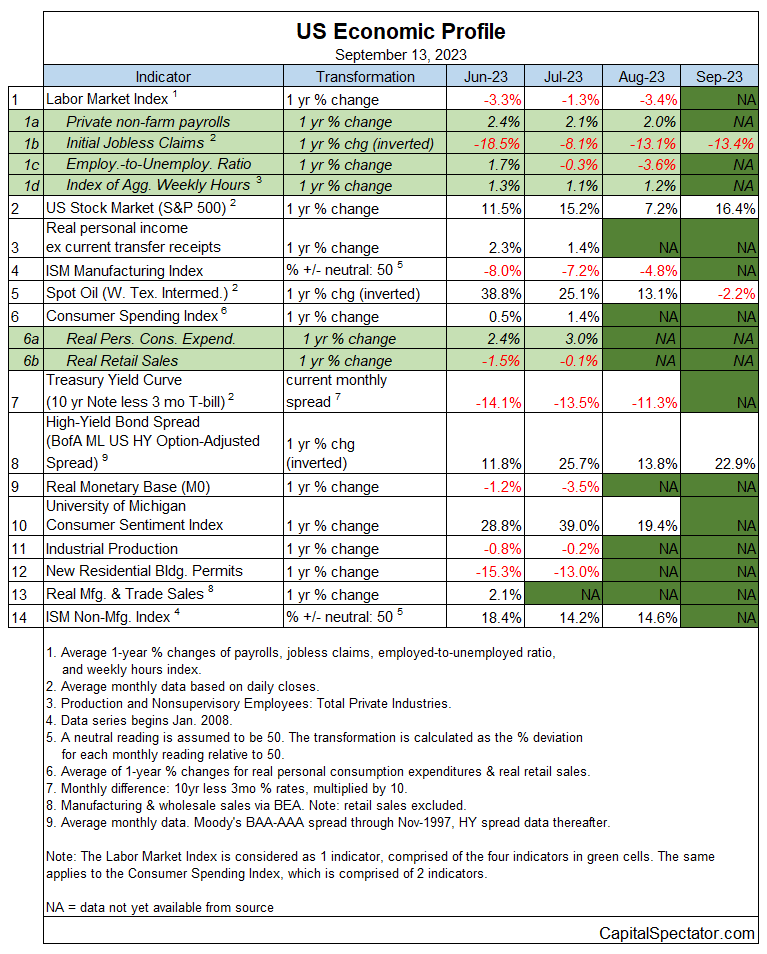

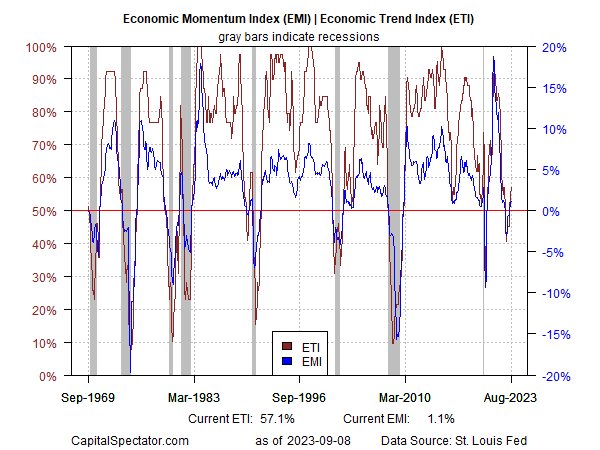

That’s the basic idea in a pair of proprietary business cycle indicators that are updated in each weekly edition of The US Business Cycle Risk Report, published by CapitalSpectator.com. The individual components of the Economic Trend Index (ETI) and Economic Momentum Index (EMI):

Aggregating the data sets in the table above shows that a modest growth bias continues to prevail in the US as both ETI and EMI hold above their respective tipping points (50% and 0%, respectively):

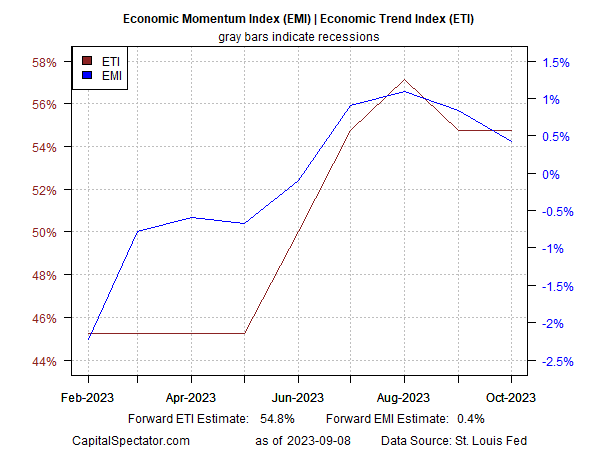

There are hints that the latest run of growth for the US economy is peaking, based on forward estimates of ETI and EMI through October.

It’s too soon to know if the peaking is noise or the start of a deeper decline that eventually ushers in the recession that so many analysts have been looking for.

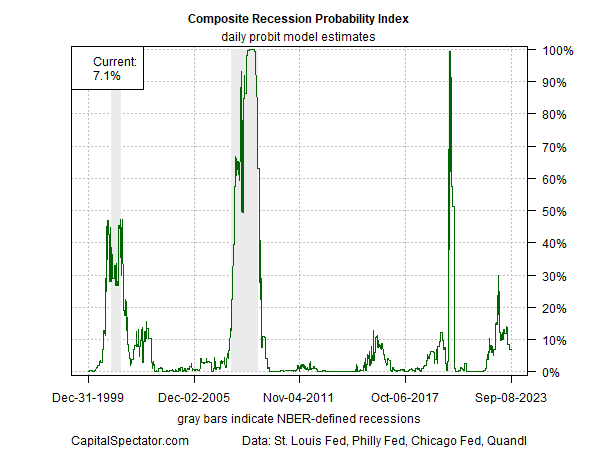

But for now, the probability that a recession has started, or is about to start, remains low, based on another indicator featured in The US Business Cycle Risk Report. The Composite Recession Probability Index (CRPI) aggregates ETI and EMI, plus three other business cycle indicators (including two from regional Fed banks), for a robust real-time estimate of US macro conditions. The current reading: the probability that the US is in recession is a low 7%.

There’s another recession lurking in the future, but a careful review of a range of indicators continues to suggest that the start of the next downturn is still beyond the immediate horizon. That forecast/analysis is subject to change as new numbers are published, which is why it’s crucial to routinely update the modeling. Meanwhile, the one thing you shouldn’t do is make forecasts that conflict with the majority of a broadly diversified set of predictors.