From time to time, I like to point out errors that we make because we think in nominal space, or because we had 25 years of inflation being so low that we didn’t have to think about it very much.

I do think that at some level, we should consider pointing the finger at economics education, which teaches static equilibria until you get into fairly advanced (graduate level) classes – and even then, generally in nominal terms.

There’s a very good videocast that I like to check in with occasionally, by Altos Research, which runs through recent data on home buying trends along with useful commentary.

It tends to be more thoughtful and not fall victim to the wild swings of emotion that seem to affect a lot of housing market observers. I think it’s important for me to say that I like this channel since I’m about to criticize an episode they recently put out.

It was called ‘Why Aren’t Home Prices Falling?’ and you can find the quick 15-minute video at the bottom of the article. You can get a good feel for the videocast, and the useful analysis they bring, from this episode.

But the question ‘why aren’t home prices falling?’ is an odd one. Median CPI is still running at 4.2% y/y. Sticky CPI is +4.1%. Apartment rents are +5.0% and never declined y/y, even when there was a rent moratorium.

Asset prices in general are quite a bit higher over the last few years also, so whether you’re looking at homes from the standpoint of an investment or a consumption item, it’s hard to see why one would naturally default to ‘home prices should be falling.’

The thought process is that ‘home prices went up so much, no one can afford them! Therefore, prices should fall.’ This thought process does not originate with Altos; they are just trying to answer the question being asked. In my view, though, they aren’t answering the right question.

When you think about it, the whole framing of the question evokes Yogi Berra saying that ‘no one goes to that club anymore because it’s too crowded.’

Home prices going up a lot is a pretty serious piece of evidence that supply and demand has previously cleared at a price that (it is assumed) is too high for people to afford. That should sound odd.

The thought process goes further by noting that the volume of transactions has really declined markedly over the last couple of years, thanks to high interest rates keeping supply off the market as homeowners with current low interest rates locked in recognize that buying a new home would involve an effective refinancing to more expensive money.

But if that restriction in supply is the main reason that home prices didn’t decline, then why have home prices in Australia and the UK also generally been rising, except for a dip around the same time that we had a dip in the US? Australian mortgages are normally floating-rate, and in the UK a 5-year fixed rate is the standard.

But the low y/y change in Australia (according to the Dallas Fed’s index of Australian home prices – don’t ask me why they track Australian home prices) in 2023 was -4.3% (now +7.7%), the low in the UK was -2.5% (now +2.2%), and the low in the US was -3.4% (now +2.9%, using Existing Home Sales Median y/y). All of those markets saw very large rises, small and brief declines, and are now rising again.

These are very different property markets, very different mortgage markets, very different governments, taxation regimes, populations, and yet they have strikingly similar patterns of home price changes in a market that classically is all about ‘location, location, location.’ This should lead the thoughtful analyst to think that there’s something else going on.

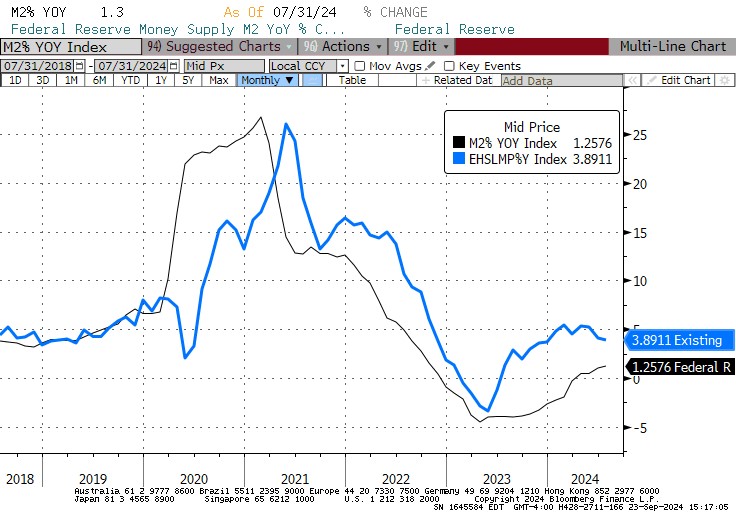

Something else – not to beat a dead horse again – is the change in the quantity of money, which has followed a very similar pattern in every major economy in the years after 2019. And this is where conventional Economics education falls short. Here is a chart of the y/y changes in US M2, alongside the y/y change in Existing Home Median sales prices.

Not all of the price changes you are seeing in homes is a ‘real’ price change. Much of what you are seeing is a change not in the value of a home, but in the value of the currency unit relative to durable physical assets. But in Econ 101, they’d tell you that you should look at changes in supply and demand, and that will predict changes in the price and quantity at which the market clears.

In that narrow frame, you might look at the large increase in home prices and attribute it to changes in demand due to declining interest rates, although you’d be confused when the massive increase in interest rates caused only a modest and temporary drop in nominal home prices. (In late 2022, the Case-Shiller futures for end-of-2023 were pricing in a 19% decline in nominal prices with inflation at a positive 3-5% per year, implying an unprecedented collapse in real prices).

That frame doesn’t make sense when the underlying price level is rapidly changing, and the underlying quantity of money is rapidly changing. This is often more obvious when we make it extreme. Suppose the money supply went up 400%, and prices quintupled as well, and interest rates went to 100%. Would you expect home prices to decline in nominal terms?

That would be absurd – the price level going up by a factor of 5 means that the value of the measuring stick is what is changing. And remember, it is entirely consistent to have the volume of transactions decline sharply while the nominal price increases. Homebuilders care about the volume of transactions; homebuyers care about the price. You may be absolutely bearish on homebuilders, while still expecting home prices to increase, especially if the price level is increasing.

That’s exactly what we have been experiencing. And, with the money supply growing again and median prices still rising at 4% per year, it does not seem to me that there is any natural reason to expect home prices to decline. So the short answer to the question ‘Why Aren’t Home Prices Falling?’ is ‘There’s no reason they should.’

Markets are where risk clears, not where investors ‘expect’ prices to be, and there were wonderful gains to be made even well into 2023 by helping the nervous real estate longs clear their risk.