By Geoffrey Smith

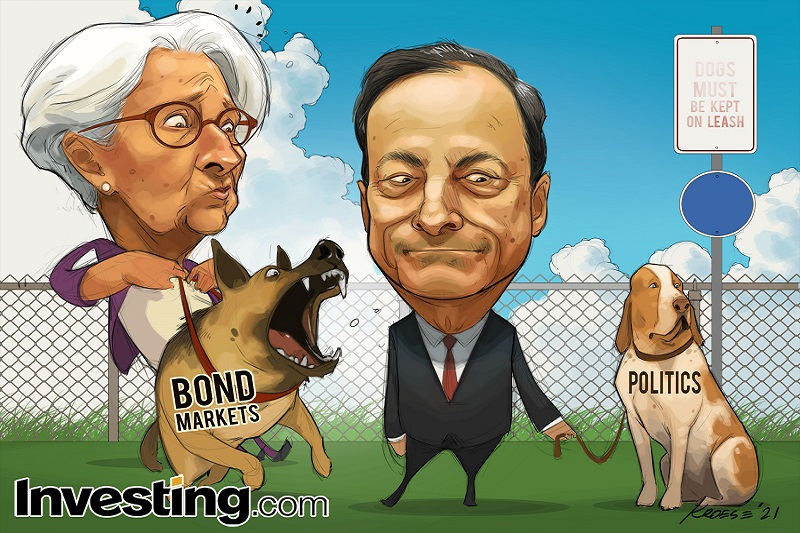

Investing.com -- It seems the bond market can still bite. It can even bite the hand that fed it generously for eight years.

But was what happened in European sovereigns last week just a reflex reaction, born of ancient instinct, or was it a more ominous sign of things to come?

Just as importantly, was the market just giving a friendly nip to its old friend, Italian Prime Minister and ex-ECB President Mario Draghi, or was it warning him that there are limits to how far even he will be indulged?

Italian and Greek bonds had their worst one-day sell-off in over a year on Thursday, and on the flimsiest of pretexts. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde, asked a routine question about the future course of the ECB’s interest rates, was deemed by many listening not to have pushed back firmly enough against the suggestion that they may one day have to rise.

The market responded by selling Italian debt heavily, pushing 10-Year yields up by 25 basis points to their highest in 15 months. The notorious ‘Spread’ – the premium over German bonds that is the barometer of Eurozone breakup risk – also rose as high as 135 basis points, its highest in over a year.

That followed months of unprecedented calm, in which it had drifted between 97 and 109, as the ECB’s bond buyers squashed any hint of the pandemic causing a systemic crisis.

So why the sell-off now? Lagarde’s lapse in communication was – at most – a sin of omission. It was nothing compared to the famous gaffe in her first press conference when she said that “the ECB isn’t there to close the spread,” a comment that went against eight years of Draghi-era ECB policy and triggered the last halfway serious sell-off.

The EU has already approved Italy’s (read: Draghi’s) post-pandemic reform and rebuilding plan, which earmarks over 200 billion euros ($232 billion) of EU money for Rome. That’s a luxury no Italian Prime Minister has ever enjoyed. That's despite the fact that, at over 5% of GDP, next year's budget deficit is clearly unsustainable in the medium term. Fortunately for Italy, the risk of the EU Commission re-imposing strict limits on government borrowing is small as long as compatriot Paolo Gentiloni holds the key Economic and Monetary Affairs portfolio. The prospect of a less fiscally-hawkish government in Berlin is also timely, in that regard. As long as Draghi runs the show in Rome, Italy's credit will always be good in Brussels and Frankfurt, it seems.

But how long will that be? As the pandemic emergency fades (Italy’s economic rebound this year had been no less vigorous than France’s or Germany’s – in sharp contrast to 12 years ago), the discipline of Italy’s warring political parties will inevitably fray. Already, party leaders such as Matteo Salvini are jostling for a return to more competitive politics, seeking to push Draghi to the sidelines.

Moreover, Draghi’s authority already seems to be weakening a little, albeit from an unexpected corner. The collapse last month of talks to sell troubled bank Monte dei Paschi di Siena to Unicredit (MI:CRDI) was a rare but significant defeat. Protests against his vaccine mandate – the world’s first to cover both private- and public-sector workers have been large and unruly - the kind that can do serious damage to leaders without a direct democratic mandate.

The solution already appears to be taking shape: In January, the venerable Sergio Mattarella’s term as President ends. Draghi has so far dismissed suggestions that he would allow himself to be nominated as Mattarella’s successor, saying that he wants to stay until parliamentary elections in 2023. However, it is an office that fits his stature within Italy, and one that still allows him to exert a less direct, but – given the frequency of Italian government crises – still important influence.

As long as Draghi is involved at some level, then the risk to Italian bonds – and Italian assets in general – from here, looks contained. The lesson of the last 10 years is that no Italian government can survive without the support of the ECB, and that Draghi is uniquely placed to maintain relations between the two. But whatever the final arrangement in Rome, last week’s sell-off is a reminder that a solution should be found sooner rather than later. The bond market has already told Australia that central banks can’t defy them forever, and it may bounce the Bank of England into tightening monetary policy later this week, too. The days of zero volatility look like being over. The need for a calming hand like Draghi’s will soon be greater than ever.