By Geoffrey Smith

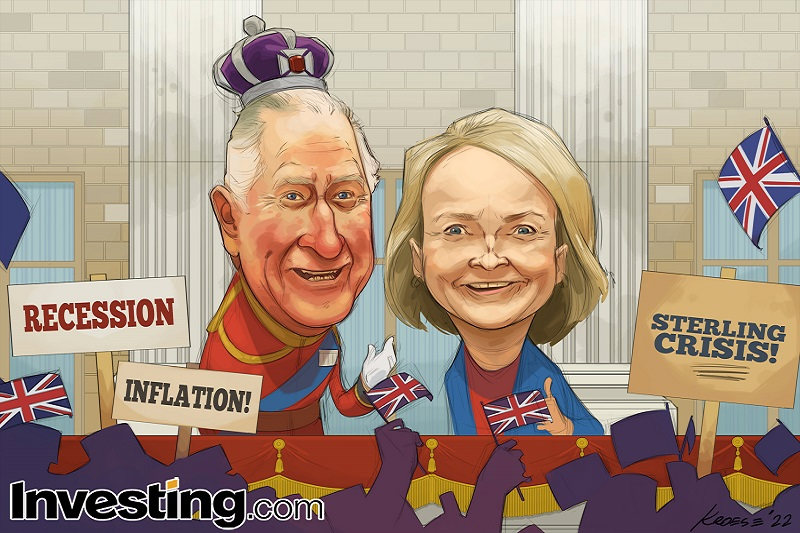

Investing.com -- "God save the King!" may have been on British policy-makers' lips last week, but in their hearts you would just as probably have found the thought "God save the pound - because not much else can!"

Sterling has had a wretched year, sliding 15% against the dollar to hit its lowest since 1985. It's also lost over 3% against the euro - a currency with real interest rates still around -8%. That is some achievement.

The reasons are, by now, familiar - some short-term ones, but more longer-term ones.

The most immediate - as discussed here recently - has been the terms of trade shock from the surge in global energy prices this year. Britain, like Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Germany, is a big net importer of energy, having depleted its natural resources of oil and gas over the last 40 years. With a large part of the U.K.'s power system dependent on natural gas, the eight-fold increase in gas prices this year has hit the U.K. harder than it has some other European economies.

Then there's the pandemic. The U.K. spent more to cushion the impact of Covid-19 - around 20% of gross domestic product, according to International Monetary Fund data - than any other advanced economy bar the United States. The fiscal deficit has widened accordingly, and the government now has more work than most to get it back under control.

As such, sterling's depreciation, along with that most European currencies, is in large measure a delayed expression of the reality that the pandemic profoundly weakened the economy - by killing, incapacitating, or simply taking out of the workforce hundreds of thousands of productive individuals.

The Office for National Statistics said on Tuesday that the inactivity rate - that part of the working age population that is not in the workforce - hit a seven-year high of 21.4% in July, largely due to long-term sickness among 50-64 year-olds. This isn't just the direct effect of Covid, but also the extent to which many people's pre-existing conditions worsened during the pandemic due to a combination of scarce resources and administrative inflexibility.

Admittedly, the ONS also said that employment rose to a new record high of 29.66 million in August. But a look at longer-term data shows that productivity, the ultimate driver of higher living standards and returns on capital, has slipped chronically into a slower gear: Output per hour worked has risen only 7% since the first quarter of 2008.

That is the situation inherited by the U.K.'s new Prime Minister Liz Truss, whose first act has been to announce a plan to keep the lights on that may end up costing another 5% of GDP (the figures are largely guesswork since the government hasn't detailed its estimates yet and - more cheerily - wholesale energy prices appear to have peaked in the near term).

Bond markets, lulled to sleep by years of being backstopped by the quantitative easing strategies of central banks, have had a rude awakening. Truss's likely borrowing needs sit uncomfortably with the fact that the Bank of England wants to start selling 10 billion pounds of bonds a quarter, net, out of its QE portfolio into the market. The yield on the 10-year benchmark Gilt now stands at an 11-year high after rocketing 1.3 percentage points in the last two months.

A huge budget deficit and a huge current account deficit, in an environment of rising inflation and interest rates, is a combination fraught with risk. Deutsche Bank (ETR:DBKGn) analysts warned last week that it could end - as it did 45 years ago - with a bailout from the IMF.

Barclays (LON:BARC) analysts, however, think such talk is overdone. The terms of trade story is a global one, rather than sterling specific, they argued in a note to clients at the start of the week.

"We would be more worried if risks linked to EU trade relationships were to lead to a tariff war," they added.

On this, at least, the news flow since Truss's elevation has been positive. Fighting talk at the hustings about triggering the infamous "Article 16" of the U.K.-EU Brexit deal, unilaterally overriding it with new legislation, has been replaced by more conciliatory talk in newspapers sourced to unnamed insiders, who appear unwilling to risk a blow-up with the EU at this moment in time.

That may not have been the reason for the pound's turnaround in the last couple of days, but nor has it harmed it either.

Even so, as with the new sovereign whose face will now be printed on it, the pound has some hard work ahead of it over the rest of the year. Truss will be thankful that, unlike Charles III, it should be relatively easy to improve on her predecessor's record.