My interview on Bloomberg last week started with a trillion-dollar question:

It is important that we don’t just look at a GDP number and say, “Oh, it’s almost 3%,” and move on. We need to stop and ask, “Why is growth so good?”

To answer it, let's focus on the pickup in productivity growth in recent years and how policymakers can keep it going.

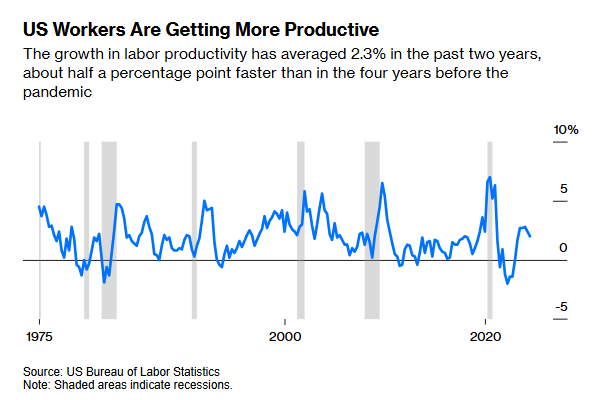

The gains are impressive. The growth in labor productivity, which has averaged 2.3% in the past two years, is about half a percentage point faster than in the four years before the pandemic.

While it may not sound like much, that difference would shave almost 10 years off the time it takes to double the level of real GDP.

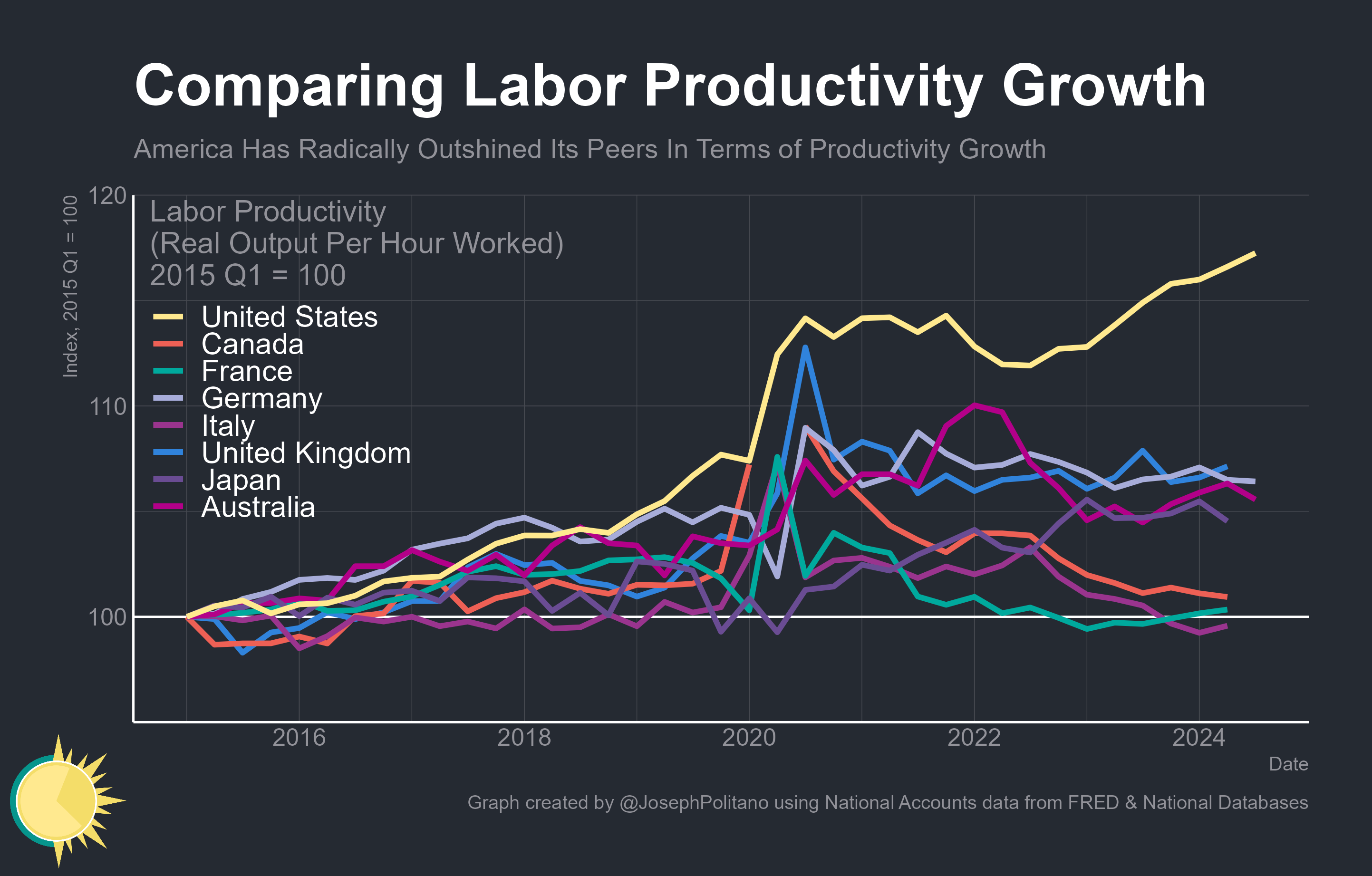

The US stands out globally. Joseph Politano’s excellent piece on productivity shows that the gains in the US are unlike any of our peer countries.

The underpinnings of inflation since the pandemic have received orders of magnitude more attention than the underpinnings of productivity. That’s a mistake.

Break Down Barriers

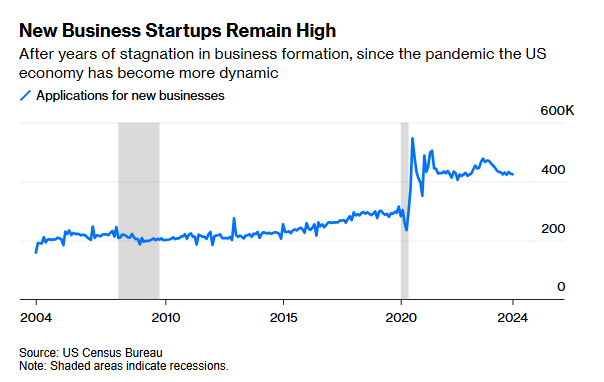

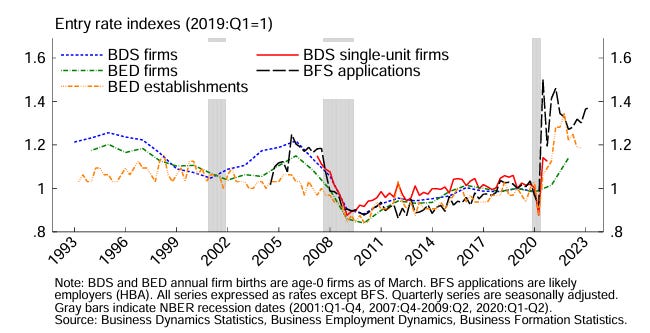

There are many components to the productivity increase. One of them is likely the notable increase in business formation since the start of the pandemic.

When applications spiked early in the pandemic, there were questions about what it meant and the staying power.

Impressively, as Decker and Haltiwanger document, the increase in applications did turn into an increase in new businesses (with employees), and most importantly, the faster pace lasted beyond the early years of the pandemic.

After decades of a falling startup rate, since the pandemic, the US economy is slowly becoming more dynamic with more younger firms. An important question is why the increase in new businesses happened and whether it can be extended. My piece mentions some of the possible causes:

The initial burst of business formation early in the pandemic appears to have been a reaction to the large shifts in economic activity due to the public health emergency and a shift to remote work. Pandemic relief policies also appear to have had the unintended consequence of lowering the financial barriers to starting a business.

In fact, there is evidence that stimulus payments and other income support boosted entrepreneurship. Areas with higher populations of Black Americans, often underrepresented among business owners, were particularly likely to see an increase in applications, suggesting how powerful it can be to lower barriers to entry.

While we should not expect another round of fiscal relief, one lesson from the pandemic is that policies that reduce barriers to entry can have sizable effects on creating new businesses. The incoming administration should apply that insight to its deregulation agenda.

Lowering entry costs and promoting competition through better regulation could similarly support productivity. Interest rates can raise the costs of starting and growing a business, so the Fed must be careful not to choke innovation with higher interest rates than necessary.

Dynamic Labor Markets

Another likely source of the recent pickup in productivity is the strong labor market during the recovery. Again, here is from my piece:

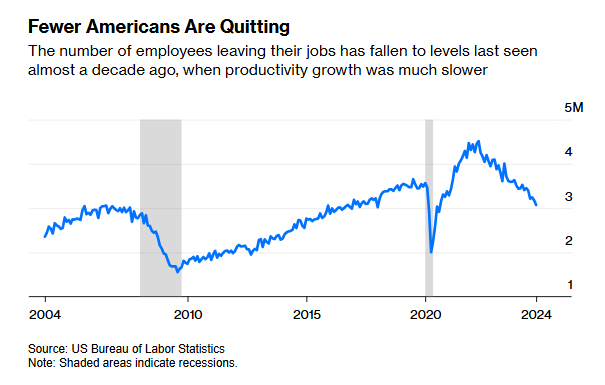

The productivity pickup is not just about new, innovative firms. It’s also about workers moving to jobs that better match their skills. While disruptive, the so-called “Great Resignation” of 2021-22 allowed many workers to move to jobs that allowed them to be more productive.

Researchers have pointed to the high churn of workers earlier in the pandemic as a key reason for the recent upturn in US productivity. New business applications were also higher in industries and geographical areas with higher levels of job-quitting. A dynamic labor market is directly tied to a dynamic business environment.

The remarkable movement of workers may also help explain why the US, but not its peers, experienced a productivity boom.

The US offered generous income support during the pandemic but did not prioritize keeping workers with their employers in the recession, such as in countries like Germany.

The subsequent rapid recovery in demand in the US was met with many workers moving to better-paying (more productive) positions.

What’s the lesson for now to extend the productivity gains? A dynamic labor market is central to a dynamic economy. The cooling of the labor market, albeit gradual, is also a cause for concern.

The rate of employees quitting jobs (often to move to a new opportunity) has fallen back to levels last seen in 2015, when productivity growth was notably slower. Moreover, the quits rate shows no signs of stabilizing.

It’s not the dramatic weakening common in a recession, but protecting the dynamism of the labor market should be a priority. Over the summer, the Fed correctly set “no further cooling” as its test for the labor market.

In Closing

We need to talk about growth and understand why it’s been exceptionally good in the US in recent years. It’s not about settling the score over fiscal and monetary policy. It’s about finding ways to sustain progress.

For both the Fed and other policymakers, now is not the time for complacency. Watch the labor market and the rate of business formation: If they slip back and become less dynamic, productivity and supply-driven growth could slip away, too. The US economy has come too far in the last few years to allow that.

Original Post

Link to Interview