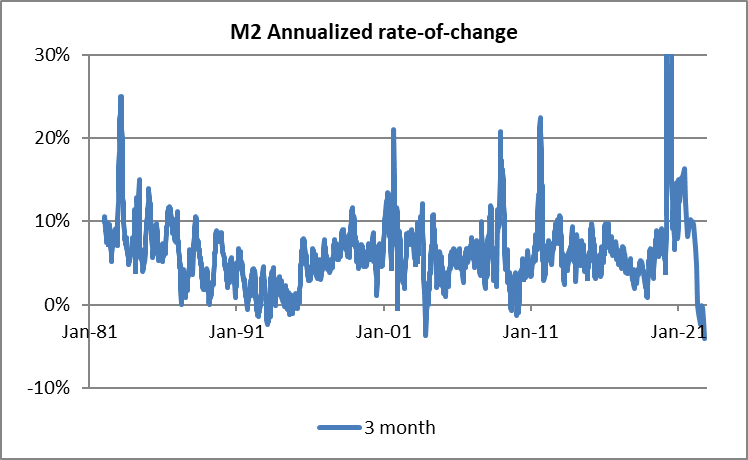

Last week, the Fed reported that the M2 money supply declined, slightly, again. The year-over-year rate of change is now down to a paltry 1.3%.

Source: Bloomberg

Not only that, but the quarter-over-quarter annualized rate of change (I’ve truncated the spike in 2020 when it exceeded 60%, since that messes up the chart!) is negative for only the fourth episode in the last forty years.

Sharp-eyed observers will notice that those four episodes correspond to the recession of the early 1990s, the recession post-tech-bubble, the recession after the global financial crisis, and the looming recession post-COVID. This is a wonderful opportunity for debate. Is it the collapse in money growth that causes the recession? Or is it recession that causes the slowdown in money growth?

Frequent readers of this column will know that I have been skeptical that money supply growth would appreciably slow for long. The reason I thought that would be the case is that I figure the elasticity of loan demand was lower than the elasticity of loan supply, and while higher interest rates would dampen loan demand a little it would stimulate loan supply a lot. (This might not be as true when the curve is inverted, to the extent that banks fund long-dated loans with short-dated borrowings.)

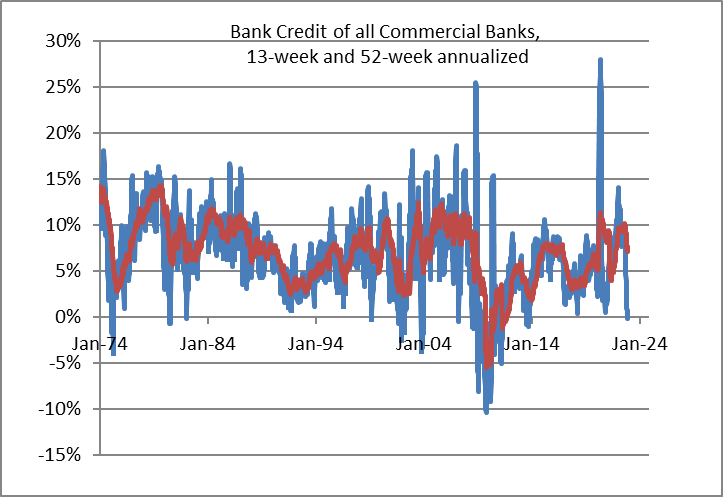

In the ‘old days,’ when monetary policy worked through the mechanism of restricting available bank reserves, Fed tightening would lower money growth but in a world where banks are not reserve-constrained the Fed’s raising of interest rates should not have the same impact on bank lending. In any event, though, bank credit is now also slowing noticeably, with a negative 13-week rate of change for the first time since 2011.

Source: Federal Reserve with Enduring Investments calculations

So does this mean greater bank caution than I expected? Or a much more serious drop in loan demand? I wonder if banks, although not reserve-constrained, are more capital-constrained than I thought (if they are mismatched, they have a long-dated loan book that’s under water compared to their short-dated liabilities and the scale of this unrealized loss will be significant in some cases). Or, perhaps, they are being more credit-conscious (at the right point in the cycle to be so) than they typically are.

But in any event, if the money supply can decline meaningfully, it means the ultimate destination for the price level will be lower. While the rate of change of money is zero or negative, the first chart above illustrates that the stock of money remains far above the prior trend—and it’s the stock of money that determines the price level. As it is, the price level is lagging the prior money growth by a lot, which to me signifies inflation momentum in the pipeline. But perhaps there is less momentum than I thought.

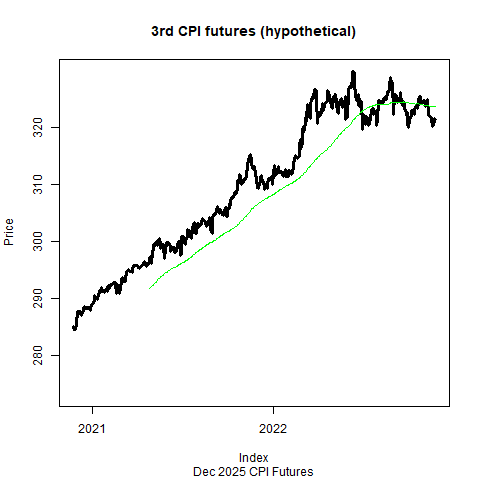

Super interesting to me is the behavior of the hypothetical December 2025 CPI futures (which don’t exist yet, but Enduring Investments calculates them based on the inflation swaps curve). The chart below covers a different time period than the first chart; the left side of this chart picks up basically right after the sharp vertical move on the first chart in mid-2020. Compare what happens to the forward price level indicated by futures when the stock of money levels off. It’s sort of uncanny: when the money stock stops increasing, so does the market-implied forward price level.

Now, I still have quibbles with the implied price level itself. The market pricing implies that the price level will not close the gap with the prior increase in the money stock. Put another way, the market pricing suggests a permanent impairment in money velocity. Velocity plunged alongside the spike in M2, but (to me) there is really no reason to expect that plunge to be permanent. Market pricing, however, disagrees with me.

Even if you also disagree with me, it probably behooves you to take a long position in that forward price level. Because if I’m wrong, the market is already pricing it. And if I’m right, there’s a lot of upside in that forward price level. I am always looking for trades where “heads I win; tails I don’t lose.” The market pricing of inflation right now looks to me like such an opportunity.

Taking a Step Back…

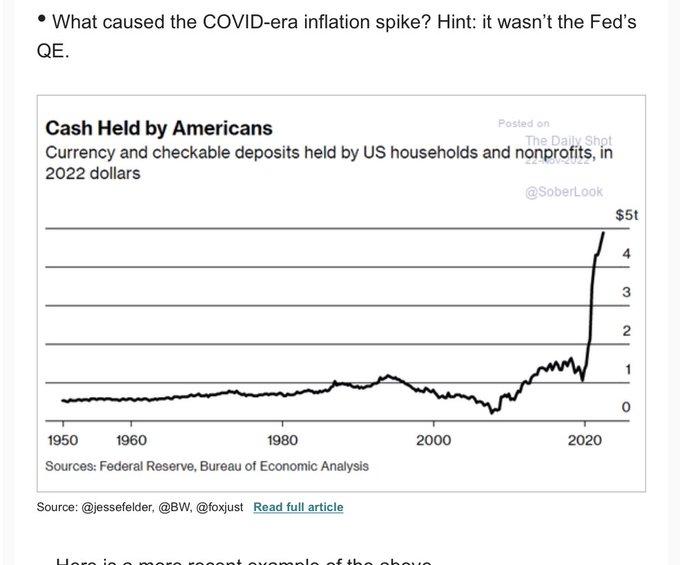

The sourcing on this next chart is a little convoluted. The chart is from @jessefelder, @BW, and @foxjust, using data from the Fed and the BEA. But the screenshot is from an email from The Daily Shot, @SoberLook. I am presenting it this way because the interesting part is the “Hint” that was added in the email.

The writer poses the question of what caused the inflation spike and “hints” that it wasn’t the Fed’s QE. But that’s ridiculous. The implication is that the legislature and the President are what caused the inflation, by squirting trillions of dollars into individuals’ accounts. And that’s definitely part of it. But where do they think the government gets the money to do that? The Easter Bunny?

In order to spend more than it takes in, the Treasury needs to borrow money. In normal times, the Treasury gets this money by issuing bonds, which are bought by the population, by pension funds, by businesses, and so on. When that happens, the net amount of cash in the system doesn’t change but only who is spending it. I would have spent money on a new car, but instead, I decided to save for retirement and bought a bond. The money I sent to the government when I bought that bond instead goes to build a bridge, or is distributed to retirees in Social Security payments, etc. But the total amount of cash in the system doesn’t change.

In this case, though, the government issued a bond that was bought by the Fed. The Fed does not need to take cash from its stock of savings; it merely creates that money with a book entry. And that means the total stock of cash increases in direct relation to the amount of reserves the central bank is creating. So, hint: the inflation would not have happened without the monetary stimulus. You may be interested to know that from February 2020, the total amount that the Fed balance sheet expanded was about $4.8 trillion. Interesting how that works, isn’t it?

Disclosure: My company and/or funds and accounts we manage have positions in inflation-indexed bonds and various commodity and financial futures products and ETFs, that may be mentioned from time to time in this column.