It’s hardly the first time that the sharp rise in interest rates over the previous two years has prompted warnings about the business cycle outlook from an economist.

Yet the forecast still resonates when it comes from a Nobel laureate, even in the wake of the latest upbeat US economic news.

The biggest short-term risk is “the central bank raised interest rates too far, too fast,” explained Joseph Stiglitz at a conference hosted by the Japan Society in New York on Wednesday (Feb. 7).

Speaking at the group’s Global Risk Forum, he said the Federal Reserve “misdiagnosed” the spike in inflation in 2021-2022, which led to sharp increases in interest rates to tame pricing pressure.

Although there are signs that the policy tightening is succeeding as a contributing factor to the recent run of disinflation with limited fallout for growth, the economics professor at Columbia University still sees the potential for trouble ahead.

Stiglitz said the Fed saw inflation as a demand-side problem, but the economist told the audience it was primarily a supply-side issue.

As an example, he advised that a key factor in inflation’s rise in the current cycle has been an increase in housing prices, which accounted for roughly one-third of the price spike.

A crucial part of the solution, he added, was that the economy needed more houses to help lower prices.

Instead, by sharply lifting interest rates, and by extension mortgage rates, a hawkish turn in monetary policy created headwinds to ramping up residential housing construction.

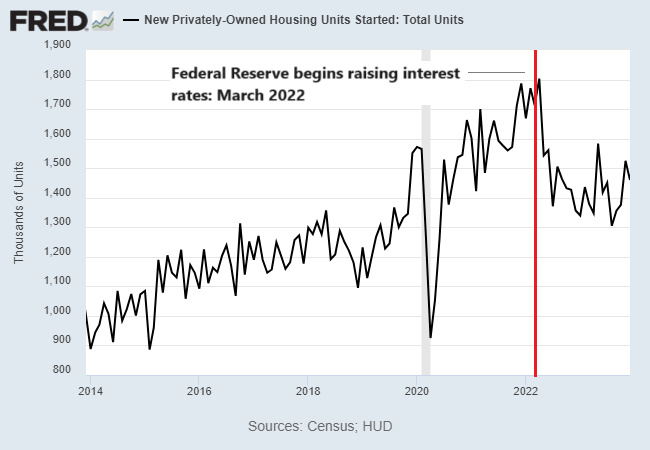

Indeed, housing starts have fallen substantially since monetary policy turned hawkish in March 2022, as shown in the chart below.

Stiglitz added that while the US economy “will do pretty well” vs. the rest of the world overall, the sharp rise in interest rates will remain “a threat to growth in 2024.”

He cites the “long and variable impact” of monetary policy as a lingering headwind, noting that policy changes can take time to fully impact the economy, for good or ill.

Stiglitz’s bona fides in the dismal science are reason enough to refrain from dismissing his warning, but for the moment the US economic profile continues to defy the darker forecasts from various corners over the past year.

Yesterday’s first-quarter estimate of US GDP via the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model (as of Feb. 7), for example, reflects a solid increase in expected output that’s in line with the stronger-than-expected Q4 rise reported by the government.

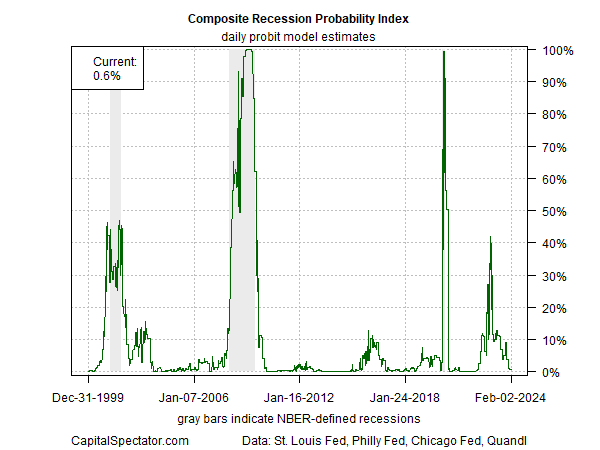

Meanwhile, CapitalSpectator.com’s sister publication – The US Business Cycle Risk Report – continues to estimate the probability that an NBER-defined recession has started or is imminent at a low 1% (as of Feb. 2), based on the Composite Recession Probability Indicator, which combines estimates from several models.

Looking beyond the immediate future in the cause of making high-confidence forecasts is extremely challenging for business-cycle analytics and so caution is recommended on this front.

Nonetheless, Stiglitz’s warning isn’t easily dismissed. But if we forgo forecasts, the current numbers strongly suggest that recession risk is low – a profile that even a Nobel-prize-winning economist would have a hard time refuting, at least for now.